Weber Siphon - overview

“Although the Bureau took steps to preserve the salmon, had its measures failed, it was ready to see the salmon disappear, . . .”

- Paul Pitzer, “Grand Coulee - Harnessing a Dream”

On February 17, 2009, President Obama signed the America Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), Title IV of which appropriates $1 billion in funds to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation for developing water projects. P.L. 111-5, 123 Stat. 137.

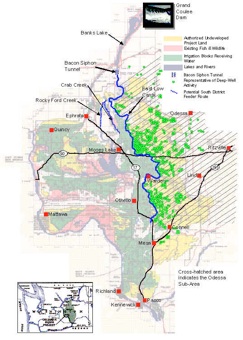

In April 2009, the Bureau allocated $50 million (5 percent of its ARRA appropriation) to expand a large, Columbia Basin water pipe called the Weber Siphon. The Weber Siphon expansion will double the capacity of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project to transport Columbia River water underneath the Interstate 90 freeway for irrigation. (See map)

Losses to Taxpayers and Ratepayers

This $50 million water pipe is part of the story of the Columbia Basin Project (CBP) -- the largest all-federal irrigation project in the United States. Massive public subsidies are expended to pump water to CBP irrigators, including taxpayer support for the cost of the project and Bonneville Power ratepayer subsidies for the energy it takes to pump water uphill from Lake Roosevelt into Banks Lake.

In the early 1990s, the Bureau shelved proposals to expand the Columbia Basin Project when independent economic analyses revealed huge losses to taxpayers and ratepayers. (see ”Water Project Subsidies: How They Develop and Grow” and GAO Review). In 2006, however, the Bureau dusted off its old CBP expansion plans , and is aggressively moving forward. The Weber Siphon is part of the Bureau’s overall plan to expand the CBP.

The Bureau's water pipe sleight-of-hand continues a strategy begun under the Bush Administration: expand the CBP by planning and building a series of individual projects, but never revealing the connected whole. Thus the public remains uninformed about the total costs to taxpayers and ratepayers, and the impacts to the Columbia River and salmon.

Nearly 10 times the water needed

The Weber Siphon was originally designed to include two large pipelines or “barrels” but only the first barrel was built. The Weber Siphon expansion would add 1,950 cubic feet per second (cfs) in water capacity to the East Low Canal, more than doubling capacity to 3,650 cfs. For flow comparison, summertime low-flows for the Spokane River (at the Monroe Street gage in downtown Spokane) range from 500-900 cfs.

The Bureau’s announcement of stimulus funding for the Weber Siphon Project describes the project as connected only to the Lake Roosevelt Drawdown. The Lake Roosevelt Drawdown requires about 200 cfs of additional water to be moved underneath Interstate 90 freeway to serve 10,000 acres south of I-90 and east of the current CBP service area.

Importantly, the Bureau’s announcements regarding the Weber Siphon Project fail to acknowledge that the water pipe is also connected to and necessary for the Odessa Subarea Special Study. The Odessa Subarea Study is examining the potential for bringing water to 140,000 acres east and southeast of Moses Lake - a major expansion of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project.

While the Bureau’s Stimulus Funding documents deny any connection to the Odessa Subarea Study, other documents clearly do make the link. Of greatest significance, the Bureau’s April 2008 Odessa Subarea Appraisal Report acknowledges that the two cheapest water delivery alternatives would require expansion of the Weber Siphon.

The fundamental question is: where is the water coming from that will fill the Weber Siphon? The answer: the Columbia River. But, water is not available for more water withdrawals from the Columbia River. NOAA Fisheries requires “bucket for bucket” mitigation for water taken from the Columbia River. The National Academies of Science (Managing the Columbia River: Instream Flows, Water Withdrawals, and Salmon Survival, 2004) recommended that the Department of Ecology not authorize new water diversions from the Columbia River.

Existing water diversions, dams, habitat loss, and water quality problems are already contributing to the decline in salmon. Climate change looms large as a threat to what remains of the salmon ecosystem of the Columbia River. Yet despite the warnings from the NAS, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and Washington Department of Ecology continue to plan more water withdrawals from the Columbia River.

The Bureau and Columbia River Salmon

The Columbia River was once home to the greatest salmon runs on earth. Dams transformed the Columbia River into a series of slack-water reservoirs. The Grand Coulee Dam/Columbia Basin Project devastated the salmon ecosystem of the upper Columbia River. The Bureau fits prominently into this history of salmon destruction. Columbia Basin Project historian, Paul Pitzer, noted:

Although the Bureau took steps to preserve the salmon, had its measures failed, it was ready to see the salmon disappear, deeming the economic contribution of the dam as far more important than the fish. This attitude showed from the start. The Bureau of Reclamation took control of Grand Coulee late in 1933, but squabbled for over three years with the U.S. Department of Fisheries and the State of Washington over the preservation of fish runs before taking any action. The delay was almost too long, and overcoming the difficulties it created required experimental, expensive measures. (Grand Coulee: Harnessing a Dream, WSU Press, 1994, p. 223-224, reprinted with permission of the author.)

In the 1930’s, the Bureau decided to "mitigate" the CBP's devastating impact on Columbia River salmon runs by constructing fish hatcheries. These hatcheries have created a whole new set of problems, especially at the Leavenworth National Fish Hatchery, where the hatchery de-waters a reach of Icicle Creek, preventing passage of ESA-listed bull trout and steelhead.

Need for Political Leadership

CELP, Sierra Club, and Columbia Riverkeeper have alerted key members of Congress and the Obama Administration to the Bureau’s problematic management of the Columbia Basin Project (Letter, May 4, 2009).

East Low Canal & Interstate 90. The canal carries water roughly parallel to I-90. The Weber Siphon moves water underneath the interstate freeway. (John Osborn photo)

Pipe under construction to move more Columbia River water under Interstate 90: Weber Siphon. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation has long sought to expand federal irrigation in the Columbia Basin Project. USBR has evaded the required cost-benefit analysis. (John Osborn photo, October 24, 2010)

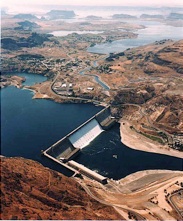

Grand Coulee Dam diverting water from the Columbia River - at huge costs to taxpayers and ratepayers. Using energy from dam powerhouses, the Bureau pumps water uphill to Banks Lake (right upper image) and to the canals of the Columbia Basin Project. (US Bureau of Reclamation photo)

Columbia Basin Project. The CBP is the largest all-federal irrigation project in the United States. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation has long sought to expand the Project - at a substantial cost to taxpayers and electricity ratepayers, while further endangering salmon of the Columbia River. (John Osborn photo)

Columbia Basin Project (CBP) & Weber Siphon (click here to enlarge map). The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation diverts water from the Columbia River at Grand Coulee Dam, pumps it uphill, and delivers water through canals to the Columbia Plateau. The East Low Canal (shown in blue) crosses Interstate-90 through the Weber Siphon.

Columbia River, Hanford Reach